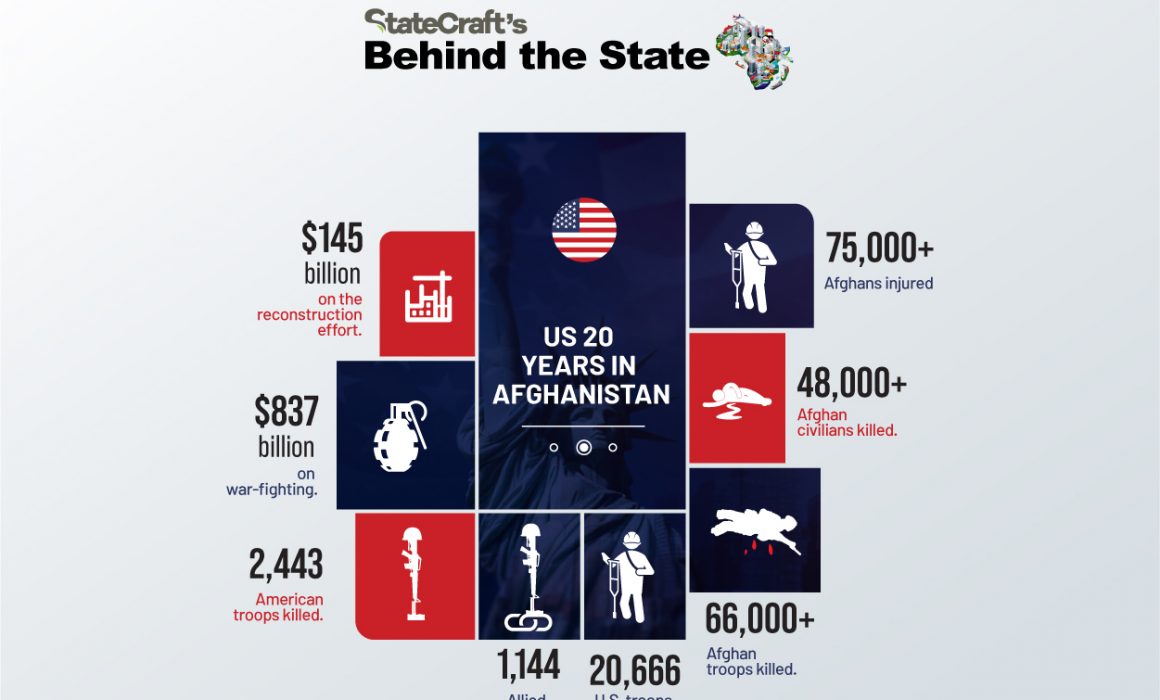

Amid Tension: Nation Building Lessons from Afghanistan

As we watch the tragedy unfolding in Afghanistan, American forces having spent two decades there, we recognize that there have been bright spots—such as lower child mortality rates, increases in per capita GDP, and improved literacy rates; but amid the current tension, there are many lessons for African leaders to learn.

Nation-building requires a strategy

One of the struggles of the U.S. government was the inability to develop and implement a coherent strategy for what it hoped to achieve. The division of responsibilities among government agencies was not clearly articulated to factor in each agency’s strengths and weaknesses. Poor division of labor between the Department of State and Department of Defense (DOD) resulted in a weak strategy. In Nigeria, issues on the duplication of responsibilities and the need to clarify MDAs duties have been raised in the report of the Restructuring and Rationalization of Federal Government Parastatals, Commissions and Agencies, known as Oransanye’s report but little has been done to implement the recommendation provided. It is important African countries understand nation-building requires the effort and alignment of all agencies.

Nation-building requires time

Analysts miss it when they think the US had a 20-year strategy for Afghanistan reconstruction. In reality, it can be described as ‘20’ one-year reconstruction efforts, rather than one 20-year effort. We often underestimate the time and resources needed to rebuild a country, leading to short-term solutions that complicate the issues.

Nation-building requires context

To effectively rebuild Afghanistan or any country, a detailed understanding of the country’s social, economic, and political dynamics is required. The difficulty of collecting the necessary information does not mean settling for less or creating strategies without data. In the case of Afghanistan, the United States’ sparse knowledge of the local context meant projects initiated to mitigate conflict often escalated it -and even inadvertently empowered insurgents.

Nation-building requires monitoring and evaluation

Projects, programmes and funds invested for implementation should have an impact on the country. Through monitoring and evaluation, stakeholders would identify what works, what does not, and what needs to change as a result of events. This is particularly important in complex and unpredictable environments where there are multi-dimensional conflicts. The absence of periodic monitoring and evaluation in Afghanistan created the risk of repeating the wrong things and hoping for a different outcome. According to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction report, “the U.S. government’s M&E efforts in Afghanistan have been underemphasized and understaffed because the overall campaign focused on doing as much as possible as quickly as possible, rather than ensuring programs were designed well, to begin with, and could adapt as needed.”

Nation-building requires a holistic strategy

As Gen. David Petraeus, who commanded multinational forces in both Iraq (2007–2008) and Afghanistan (2010–2011) and later directed the CIA (2011–2012) rightly said, “if you want to really deal with the problem, you can’t counter-terrorists like Al Qaeda or the Islamic State with just counter-terrorist forces … the key there is that you have to have a comprehensive approach.” That includes political brokering, restoring basic services, reestablishing local institutions, and building infrastructure.

StateCraft Inc.’s analysis of the situation in Afghanistan proves that while most superpowers overcommit themselves far from their own borders, their continuous commitment cannot be guaranteed. As events continue to unfold, this is a resounding call to African statesmen, leaders and policymakers to urgently revive the self-subsisting wheels of nation-building, rather than continuously relying on world superpowers.